Luke Steckel is finishing his 10th season with the Tennessee Titans, the very same NFL team that made its lone Super Bowl appearance with his father, Les, as offensive coordinator.

That connection didn’t get Luke Steckel into the family business.

That credit goes to a friend from college and an interview that took Steckel away from being a production assistant on “Iron Man 2″ to his other passion: football.

Les Steckel, who worked for seven different NFL teams and coaches, had nothing to do with his son getting his first football job in Cleveland. His son called his father to tell him about the interview.

“It’s funny how that stuff works out, but growing up in that environment where it’s … kind of hard to escape it,” Steckel said. “This is a fun business. There’s there’s some highs and lows, but it’s hard to match it with anything else.”

The potential downside of football as a family business, naturally, lurks in the issue of nepotism.

Fathers hiring sons or recommending them to friends on other teams can unwittingly perpetuate the sport’s long struggle with consistently placing coaches of color in the top roles.

The NFL’s annual diversity and inclusion report on occupational mobility patterns acknowledged the issue as recently as the 2020 edition, which cited internal league research that found a total of 63 coaches in the NFL were related either biologically or through marriage. Fifty-three were white.

NFL executive vice president of football operations Troy Vincent called out the issue in his introductory message published in the 2020 and 2021 reports: “Merit-based policies and practices need to be considered in order to discourage the system of nepotism that unduly influences the hiring cycle — family, agents, friend networks.”

In the 2022 edition, there’s no mention of family coaching connection statistics or acknowledgment of the nepotism issue.

Of the 35 men who served as a head coach during the 2022 season — there have been three firings and subsequent interim replacements — 12 are related to current or former NFL coaches. Research by USA Today found at least 93 of 717 on-field coaches this season (about 13%) are related to a current or former NFL coach, and 76 of those 93 family-connected coaches are white.

“The pipeline to become a head coach in the NFL is already blocked or clogged among coaches of color, and then when you add these networks and the father-son relationships that are factored in, the ability to lead an NFL team among black coaches becomes even more out of reach,” said Marissa Kiss, a researcher for the Institute for Immigration Research at George Mason University which has conducted several studies of minority hiring in sports.

Those connections can last generations. Sean McVay — grandson of former Giants coach and 49ers GM John McVay — got his first NFL job on Jon Gruden’s staff in Tampa Bay in 2008, about four decades after Gruden’s father, Jim, was hired on John McVay’s staff at Dayton.

John McVay also helped Jon Gruden get his first NFL job with the 49ers in 1990, and Gruden said before facing Sean McVay as a head coach for the first time in 2018: “It was my time to help a McVay and I wanted to give Sean an opportunity to be a coach.”

McVay got his first offensive coordinator job in Washington under Jay Gruden, after spending four years as an assistant there under Mike Shanahan — who also worked for his father in San Francisco.

Mike’s son, Kyle, also joined the family business, getting his first NFL job on Gruden’s staff in Tampa in 2004. Kyle Shanahan then worked under his father’s former player and assistant, Gary Kubiak in Houston, then as offensive coordinator under his father in Washington and now is finishing his sixth season as head coach in San Francisco.

Shanahan credits the time he spent as a kid following his father around for helping him learn the business.

“You don’t realize how much that stuff helps you until you kind of get into work and you realize the advantages you have and some of the stuff like, ‘I guess maybe I was learning as I was growing up and paying attention to a lot of stuff,’” Shanahan said. “I don’t think that’s just totally unusual with me and my dad and father and sons in football. I think that’s, if you go by percentages, I think a lot of kids follow their parents into work, especially if they have a good relationship with them.”

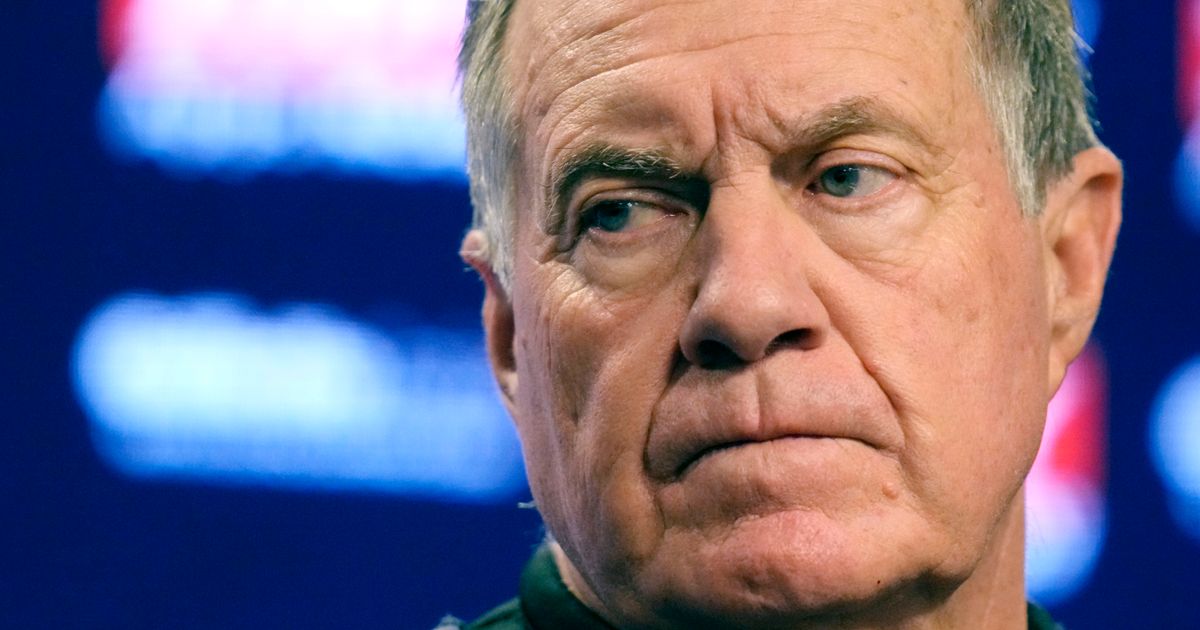

Seattle coach Pete Carroll’s son, Nate, has been with the Seahawks since he was hired in 2010 and currently serves as an offensive assistant. New England coach Bill Belichick’s sons, Steve and Brian, have been Patriots assistants for 11 and seven years, respectively. Kansas City coach Andy Reid’s son, Britt, was a Chiefs assistant before he was involved in a drunk driving crash that seriously injured a 5-year-old girl.

Previous Minnesota coach Mike Zimmer had his son as an assistant and promoted him to co-defensive coordinator. Gary Kubiak retired as Vikings offensive coordinator after the 2020 season, and his son took over for 2021. When Zimmer was fired a year ago, the staff was overhauled. New coach Kevin O’Connell brought in offensive coordinator Wes Phillips, whose father and grandfather were both NFL head coaches. Defensive coordinator Ed Donatell’s son is also a Vikings assistant.

Carroll, Belichick, Reid, Zimmer, Kubiak, Phillips and Donatell are all white. The research Kiss and her colleagues conducted at George Mason turned up only two Black head coaches who have ever had sons on staff: Marvin Lewis and Lovie Smith.

New York Jets offensive coordinator Mike LaFleur is the younger brother of Green Bay coach Matt LaFleur, who worked with now-Jets coach Robert Saleh as graduate assistants at Central Michigan in 2004. Saleh got to know Mike during lunch breaks at the LaFleur home near the campus.

“They were trying to save every cent they could because they were GAs and they knew that my parents were right down the street,” Mike LaFleur said. “So they’re going to come eat our food and watch all the TV that I was trying to watch and use our pool.”

With his Princeton degree, Steckel easily could hve gone to Wall Street. His father encouraged him to chase his passion. Steckel did that, first working in movies and then football. He worked for Mangini, then Pat Shurmur over four seasons.

Then-Titans coach Mike Munchak, who coached the offensive line during Les Steckel’s six seasons, hired Luke as his assistant in 2013. Luke stayed on staff with Ken Whisenhunt, his successor Mike Mularkey and also now coach Mike Vrabel. He promoted Luke to tight ends coach in 2021.

“It’s such a blessing, and I feel really grateful to be here,” Steckel said of spending a decade in a place he considers home.

___

AP Pro Football Writer Dennis Waszak contributed to this report.

___

AP NFL: https://apnews.com/hub/nfl and https://twitter.com/AP_NFL