GLENDALE, Ariz. — If you spend eight decades toiling to create perfect carpets of grass and end up believing that you never fully succeeded, your thoughts inevitably turn to the hereafter. George Toma’s certainly do.

For him, it seems safe to say, the Elysian fields will have yardage markers.

“When I’m in heaven, I’ll be looking at your beautiful field,” said Toma, who this week is preparing the field for the Super Bowl for the 57th consecutive year, “or I’ll be in hell looking up what kind of root system you have.”

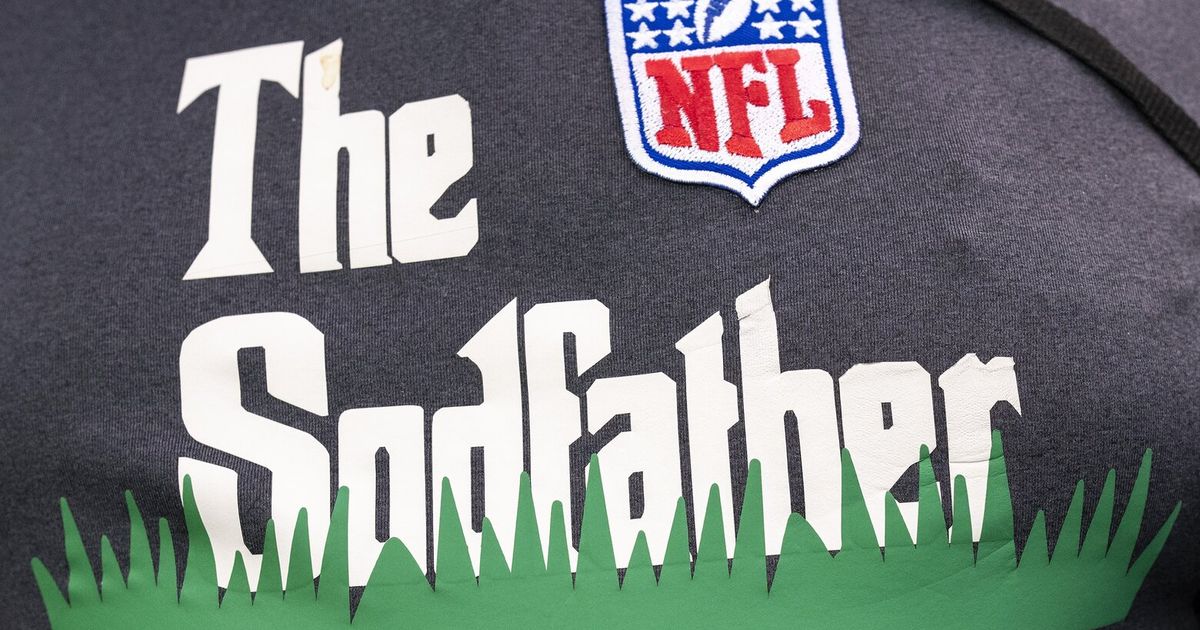

He is 94 now, but among groundskeepers he is immortal: The God of Sod, they call him, or the Sodfather, or the Nitty-Gritty Dirt Man. Toma — who is planted so deeply in the NFL’s root system that he is in the Pro Football Hall of Fame — has never missed a Super Bowl. He has worked in outdoor stadiums from Miami to San Diego and domes in Detroit, New Orleans and beyond. He has persevered through torrential downpours, droughts and, most vexingly, increasingly elaborate halftime shows that befoul his beloved turf.

On Sunday, hundreds of millions of football fans will watch the Super Bowl broadcast from Glendale and see Toma’s handiwork without realizing it. These days, he is an emeritus groundskeeper, advising his brethren on how to prepare a field worthy of the biggest event in American sports.

Still hale despite walking with a cane, he suffers from a lifelong case of perfectionism.

“For 70 years, I’ve been fighting for the cheapest insurance — a good, safe playing field for preschool all the way up to the professional level,” Toma said. “I’m sorry that I failed by not giving the people, the players, a good, safe playing field.”

His admirers say he is too hard on himself, but everyone agrees the pressure on him is real.

The safety of NFL fields became a flash point this season when players across the league urged owners to swap their synthetic fields for grass, which they consider safer and easier on the body. The league claims injury rates are roughly similar on the two surfaces.

The dispute highlighted the economic demands of the owners, many of whom opt for synthetic fields because they typically stand up better to abuse from concerts, monster truck shows and other events.

The Kansas City Chiefs and Philadelphia Eagles both play on grass at home, and they will play on grass Sunday at State Farm Stadium. But grass alone is no protection from injury. In the first game this season, which was also played in Glendale, Kansas City’s Harrison Butker rolled his left ankle while trying to kick off, forcing him to miss four games.

“There was a whole patch of turf that just completely uprooted and moved and obviously I sprained my ankle,” he said. “It’s tough because you put in a lot of work in the offseason and then all of a sudden, boom, you get injured and it’s really not on you, it’s just the surface.”

Lane Johnson, an offensive lineman for the Eagles, had better luck playing on grass. In a game against Green Bay, he said, the grass at Lincoln Financial Field in Philadelphia allowed his cleat to slide, preventing a more serious knee injury.

“With turf, if something sticks, a lot of times there is no room for error, so injuries are a lot more common on turf,” Johnson said, referring to the artificial kind. “It would be nice for it to be all grass surfaces, but I understand that comes with a cost.”

The God of Sod, it should be said, had no role in preparing either field.

Toma prefers a well-maintained grass field to an artificial one, but he praised the artificial turf field at SoFi Stadium in Inglewood, California, where last year’s Super Bowl was played, though NFL players criticized it after Odell Beckham Jr. tore a knee ligament during the game. Toma also reeled off a list of grass fields that had problems in recent years. (On synthetic fields, the groundskeepers’ work includes making sure the small rubber pellets within the turf are distributed evenly across the field.)

The key, Toma said, is ensuring that the condition of the field (and the practice fields) allows the players to perform at their best. This is vitally important at the Super Bowl.

The NFL’s biggest game was a slapdash affair at first. In January 1967, Toma was given five days, a five-man crew, a $500 budget and no instructions to prepare the field at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum for what became known as the first Super Bowl, between Green Bay and Kansas City.

He asked Commissioner Pete Rozelle for guidance.

“I said: ‘Pete, what do you want in the end zones? What do you want on the 50-yard line?’” Toma recalled saying. “He said: ‘George, it’s your field. You do anything you want.’”

Toma painted a football with a gold crown on top at midfield.

The Super Bowl quickly grew, with bigger stadiums, flashier halftime shows and larger television audiences. Yet for the first 27 Super Bowls, the NFL did not install a new field before the game, which meant Toma and his crews had to repair well-worn surfaces on a shoestring.

“We had to go to the Orange Bowl or the Cotton Bowl or the Sugar Bowl or the Rose Bowl and get the field ready nine to 14 days before the Super Bowl,” Toma said. “All we would spend is anywhere from $500 to $750 a game. Today, we’re spending $750,000.”

According to many who have worked with him, Toma has always been meticulous, hard-driving and protective of his fields. To prevent unwanted wear and tear, he used to post signs that said, “Grass grows by inches and is killed by feet.”

In other words, stay off my lawn.

“He loves what he does, and he’ll go anywhere,” said Jim Steeg, who ran the Super Bowl for nearly 30 years and worked closely with Toma. “That’s his life.”

It’s a life that began with a fateful decision: Growing up in eastern Pennsylvania, Toma decided that he wouldn’t become a coal miner like his father, who had died of black lung. To help his mother and sister, Toma worked at a nearby farm. He was paid 50 cents a day. On Saturdays, he could kill two chickens and take all the vegetables he could carry.

He learned how to water crops, prep and plant seeds and aerate the land, skills that would help him for generations.

He was a born groundskeeper. As children, he and his friends would clear a field near his house so they could play. Toma would drag springs from old mattresses across the ground to create a smooth surface. He used white coal ash for the lines.

Toma’s formal crossover from farmhand to groundskeeper came at age 12 when a neighbor who worked at Artillery Park, the home ground of the Wilkes-Barre Barons, a minor league team, hired him to help drag the infield.

Bill Veeck, the owner of the Barons and Cleveland’s big league team, made Toma the head groundskeeper of the Barons at 16. Toma spent more than two years with the U.S. Army in Korea, then returned home and worked in the minors for the Cleveland and Detroit organizations.

In 1957, the New York Yankees offered Toma a job at an affiliate in Denver. But Toma, who hasn’t seen a field he couldn’t fix, jumped instead to the Kansas City Athletics, who had one of the worst fields in baseball.

“I thought it over and said, ‘You’re going to Kansas City because if you screw up, nobody would ever notice it,’” Toma recalled.

He had no assistants, but he soon remade the Athletics’ field. A team employee had to round up 10 guys off the street and pay them $2 each to remove the tarp. For years, Toma trained students from nearby high schools. Kansas City’s weather, with wild swings in temperature, made maintaining fields difficult. He switched to Bermuda grass instead of Kentucky bluegrass and learned to pre-germinate seeds, essentially tricking them to grow faster by soaking them in water.

When the A’s left for Oakland, California, Toma joined the Royals, an expansion team. He worked for the Chiefs after they moved to Kansas City from Dallas in 1963 and readied fields for Olympic Games, soccer World Cups and NFL games overseas. He was called on to repair distressed fields at Candlestick Park in San Francisco and Soldier Field in Chicago. When the New Orleans Saints played at Louisiana State University after Hurricane Katrina, Toma brought in airboats and used their large propellers to dry the paint in the end zones.

The Super Bowl, though, has been his greatest challenge because of its high visibility. At the Super Bowl for the 1990 season in Tampa, Florida, Toma and his crew planted seed to repair the field after a college bowl game. The grass started to fill in, but was then torn up by the New York Giants and Buffalo Bills, who practiced there the day before the game. So Toma took grass from a practice field at the University of Tampa and planted and painted it overnight.

“He is the Energizer bunny,” said Ed Mangan, Toma’s successor as head Super Bowl groundskeeper. “I mean, he just never stops, he is going all the time.”

At the Super Bowl for the 1978 season at the Orange Bowl in Miami, a 120-yard tarp was pulled on the field just before the halftime show. But it was rolled out unevenly, and one end protruded past the goal post. Toma asked if anyone had a knife so he could cut away a part of the tarp to make it fit. Several fans volunteered theirs.

The next season, for the Super Bowl in Pasadena, California, Toma and his crew had to remove 800 gallons of paint that had been applied to the field for the Rose Bowl. They dug up the end zones, the sidelines and much of midfield and planted new seed. Unfortunately, heavy rain the week before the game prevented the grass from taking hold, leaving piles of seeds in the end zones.

If you spend eight decades toiling to create perfect carpets of grass, eventually time forces you to hand the responsibility to somebody else. But that doesn’t mean you stop caring.

Just about every Sunday, as the Kansas City groundskeeper Travis Hogan watches the game from the west end zone at Arrowhead Stadium, his phone will ring, and he’ll see Toma’s name come up.

“It’s kind of funny,” Hogan said. “A lot of times he will call me in the third or fourth quarter, when the game is still going on. And so obviously I can’t answer the phone because it’s loud, and it’s Arrowhead.”

He continued: “But usually he just leaves me a message and says: ‘It’s playing good. It looks great. Tell the boys they did a great job and that this old man loves them.’”